It is a rare delight to find a fragment of my own Devon family history written in the fabrics of its landscape converging with a past writer’s imagination, so it was with increasing interest that I found that the once and long-time home village of a branch of my maternal family has doubled links with literature; for not only did a famous poet of the Stuart era live there, but also a more recent novelist based one of her historical novels in the area.

I had known about Robert Herrick, the poet's, link with Dean Prior for years and sometimes mused upon the possibility that some of his verses might have embedded intriguing lost narratives about individuals from my own ancestral past. Frequently remembered for some tediously mundane and even very lewd verse, Herrick also wrote lyrical poems about flowers and rural phenomena - 'brooks and blossoms', 'birds and bowers', 'may-poles', 'hock-carts', 'wassails' and 'wakes', 'bridegrooms, brides and bridal cakes'. It seemed reasonable to suppose that his richly evocative texts encode, albeit mostly anonymously, the lives and landscapes of the locality of Dean Prior and at least one other researcher confirmed my belief that 'In the hundreds of poems comprising the bucolic scenes of Herrick's Hesperides, readers are treated to portraits of local figures as well as to images of a rural life replete with seasonal patterns, ritual repetitions, and unsophisticated naturalness.'

(In Vino-Et in Amore-Veritas: Transformational Animation in Herrick's "Sack" Poems, William C Johnson Papers on Language & Literature, Winter 2005).

Several times over the years I’d passed the village where Herrick had lived overall for a period of some 32 years. In 1629, a year after his mother's death, he was appointed the Dean Prior living and stayed in the parish until 1647, when due to his Royalist leanings. he was removed from his post. After the Restoration the poet pleaded to be reinstated at Dean; this wish was granted and Herrick returned to Devon in 1660. He remained vicar of the parish until his death in 1674.

Towards the end of her own life my maternal grandmother Annie often told me about her father’s family, the Abbotts, who were for the most part wool-combers, or wool traders who had married daughters of local yeoman farmers. There were a whole string of male Abbotts from Dean district - mostly Roberts or Johns or Williams - who, from marriages to local women had gathered other names into the genetic fold - Gidley, Legassic; Lavers; Lane; Honywell; Ford; Veal and Pearse. As I tried to imagine the Abbotts' family lives (side-tracking here if anyone is interested in genealogical research there's a short piece about the Abbotts here), I’d wondered how long my ancestors had lived in Dean and ideally conjured up scenarios in which one or more of them may have met and spoken to the poet. I’d always been rather intrigued by the village, but until recently never stopped to look around. I read with interest that a couple of centuries after the poet's demise the locals still remembered and could recite his verse - lines from which apparently were recounted down the generations. (See Gentleman's Magazine) Other rumours confirmed that, although Herrick lay in an unmarked grave his ghostly presence hovered over the place:

Herrick lay in an unmarked grave, but his lively spirit did not rest there. For the next century there were stories of his haunting Dean Prior, and a visitor who arrived therein 1810 heard "a whole budget of anecdotes about his ghost." (Two Gentlemen; the Lives of George Herbert and Robert Herrick, (available on Questia, p. 267)I wondered if Herrick’s texts and research about him and his work might provide me with much needed information about my ancestors and their lives in the surrounding area. Perhaps I could begin to fill in some gaps and solve some family puzzles.

That is as far as my interest and investigations went, until very recently, when browsing the web-archives for tit-bits of lost family history, I was able to confirm that our Abbotts -or/and families whose marriages brought them into that family - really had been rooted in and around Dean and district for at least as far back as mid to the last half of the C17, which coincides with the period when Robert Herrick was in the village. From parish registers it seems that the Abbotts may have moved down the Devon lanes to Dean from nearby Buckfastleigh, which is logical given that Buckfast was the centre of the wool producing area. There were Nicolai and Phillipi, both Abbotts; there was Richard Abbot, whose wife Jane was from the Pearse family; her mother was Dorothy Lavers. The Protestation Returns for Dean Prior for the year 1641, which are signed by the vicar, 'Robert Hearicke', is peppered with names of men whom I believe to have been our family's forefathers: William Lavers; Henry Legasick; John Honywill. This coincidence of dates prompted me to begin to look at Herrick’s poetry again, in conjunction with an increased focus on genealogical research about the family from Dean. I re-read some of the lyrics from Hesperides with new intent. Not that his comments about the locals were altogether complimentary. Anything but in fact. His poetry is replete with lines labelling the locals as ‘rudest Salvages’. Readers who may be unfamiliar with his work will know his poem 'Discontents in Devon', which begins:

More discontents I never had since I was born than here; where I have been, and still am sad, in this dull DevonshireOr, they may know his poem titled 'Dean Bourn a rude river in Devon by which sometimes he lived', in which the poet deplores both the uncultivated landscape and

uncultured people.

But recent Herrick criticism has questioned the prevailing conclusion (arising from lines in his own poetry) that Herrick hated his time in Devon, despised and ridiculed the locals, and loathed the isolated rural setting. In any case, as the editor of the new paperback Selected Poems of Robert Herrick says, many of the poems 'attest to his joy in various aspects his life in Dean Prior and to his interest in country life' (introduction) and as another blogger notes, 'Dull it [Dean Prior] may have been, and discontent he may have been, but something kept Herrick in place in Devon' (See The Reader Online).

A poem such as The Little Spinners seems to connect directly with my ancestors:

YE pretty housewives, would ye know

The work that I would put ye to ?

This, this it should be : for to spin

A lawn for me, so fine and thin

As it might serve me for my skin.

For cruel love has me so whipp'd

That of my skin I all am stripp'd ;

And shall despair that any art

Can ease the rawness or the smart,

Unless you skin again each part.

Which mercy if you will but do,

I call all maids to witness to

What here I promise : that no broom

Shall now or ever after come

To wrong a spinner or her loom.

Whilst Herrick is decidedly not the kind of poet a C21 writer would turn to in order to illuminate the lost worlds of women's lives and writings with what you might call a feminist perspective, the poem 'Spinners' does resonate with the lives of the women of the time - those whose identities are forever bound up with those of father or husband. It reminds me that several, perhaps many, of my female foremothers would have spent much of their lives inside their cottages hard at work at the loom.

I wondered whether another foremother, Dorothy Lavers, who was born in Dean in 1671, may have been baptised by the poet during his last incumbency in the parish. Perhaps indeed, her parents John Michelmore and Dawnes Michelmore were married by him the year before. Conversely, it might be possible that one, or a few, of the charmingly, ostensibly innocent often unwitting temptresses) and unnamed young girls who frequent his Hesperides - who become paradoxically, either objects of his eroticised (and even lewd) attention or recipients of his fatherly advice, were my own foremothers. Poems to 'Anthea', 'Corinna' and the mysterious 'Julia' thread the book; their presence tempts him; break his heart. Sometimes there is a hint of a fragment of an erotic frissance between poet and woman from the village, such as; 'The Suspicion upon his over-much familiarity with a Gentlewoman', a 'comely and most fragrant maid'. Or, local rural customs come to the fore merging with Herrick's Carpe Diem preoccupation, when an anonymous girl, in the guise of her pastoral name, Corinna, is bid to rise from her bed, to join her friends and other villagers in the traditional May-Day rites: 'Rise and put on your foliage, and be seen/To come forth like the spring-time, fresh and green ...'

And what, I wondered, about the clergyman who took charge of the village whilst the poet was absent; a weaver, John Syms, was vicar during the years of the Interregnum. Meanwhile after Herrick's death William Pearse took over the living. There were Pearses from Dean in our family. Could there be a link between the family branches? And I began to wonder if my woolcomber Abbott ancestors had been puritans and if so if they may have been influential in the decision to remove Herrick from his Devon post.

Above and beyond these possibilities of personal connected lived lives the poet's work also teems with evocative details of C17 Devon village life, all of which can help the family-history researcher to flesh out a context for their own personal story through the provision of authentic backgrounds for their lost forebears. Herrick's home at the vicarage is a 'little house whose humble roof/is weatherproof; his food is simple, with 'Wassail bowles to drink'; the outdoor world is adorned with 'dew-bespangling herb and tree', with 'whitethorn laden lanes whilst rural rituals come alive, with 'The harvest swains, and wenches bound/For joys to see the hock-cart crowned.

It is unlikely that I will ever find any definitive paper-trail connections between poet, poetry and personal ancestral past but there is a lasting and mutual imaginative interaction between them, which provides extra impetus and richness, both to my reading of the poems and to my pursuit of that past.

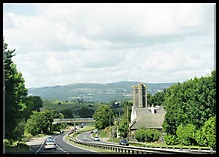

... Those who are familiar with the route of the A38 as it follows down through the South Hams of Devon will understand why most people do not stop and take a tour round Dean Prior. They will know that the road passes right next to the church, ripping the heart out of the place as it splits it in half.

The village surrounding the church, once included a school, and many cottages, these were all pulled down to build the new road through. Around the church, now lying directly to the left of the main road, had been ‘Church Town, with its cottages, church house and school and across the valley and now on the other side of the A38, lie Upper Dean and Deancombe. Lower Dean lies to the left of the A38. (The Church of Dean Prior)

|

| A38 goes by Dean Prior © Copyright Pierre Terre and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence |

They were come now to Deancombe; a cluster of steep-eaved thatched cottages, deep in rosy-fruited orchards, huddled beneath the steep bank of a bracken- gold, furze-gold,brambled hill ... She saw it now, as she stood at the top of the lane that dipped steeply down from DeanWood to Deancombe village. The smoke of bonfires drifted sweetly on the light, coolair; behind her stretched the long dark gorge of the wood, climbing densely up DeanBourne to the wild moors; unyellowed yet, it climbed, a tangled darkgreen forest of oak, birch, holly, beech and pine, on either side of the brawling river far below. Julian loved to climb up all the river's wild length, from Dean village to where the long steepravine opened out onto the purple moors at the ford where the old Abbot's Way startedacross Lamb's Down towards Buckfast Abbey in the far south. But now she turned to where Deancombe lay huddled away in rosy orchards beneath steep copses golden with furze, and beyond it to the south the blue landskip swelled and dipped. The day, the landskip, and the world were so beautiful that they burnt Julian's heart in her breast.A mysterious and mystic landscape. It's not surprising perhaps that legends such as that of the Deancombe Weaver have evolved about the locality.

|

| Bridge near DeanCombe © Copyright Tony Atkin and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence |

Dr Conybeare, a progressive-minded physician, resides in the parish of Rev. Robert Herrick. The widowed doctor lives alone with the youngest of his four children, his fifteen-year-old daughter Julian. Conybeare himself is an atheist, but the studious Julian attends church with her friend Meg Yarde, granddaughter of the local squire. Meg's brother Giles is a student at the University of Cambridge, along with Julian's brother Kit. Dr Conybeare deplores the lack of educational opportunities for women, and has Julian privately tutored in the classics by Herrick, who also instils in her a love for literature, particularly poetry. When an elderly local woman is accused of witchcraft, Conybeare and his daughter hide her in their home, but she is discovered and sentenced to be burned at the stake. The doctor administers a fast-acting poison to save her from suffering, and thus incurs the anger of the local population. Deciding to take Julian away from the hostile atmosphere of the village, Dr Conybeare arranges a visit to his son in Cambridge, and a party is made up, consisting of the Conybeares, Herrick and Meg Yarde ...Just as in her later novel The World My Wilderness, in which Macaulay 'is fascinated by the way the voices of the dead speak through the ruins of the streets and houses and buildings they once inhabited' (See Sarah LeFanu in The End of the Affair), what shines through They Were Defeated is a similar sense of someone listening for the past, who allows glimpses of the rural landscape of the real sensate Devonshire setting to resonate from behind the characters' voicing of cleverly reconstructed local dialect-speak. As Sara LeFanu, her biographer, says, by the time Macaulay wrote this novel she 'was already attuned to the ghosts' voices speaking out of history' (Rose Macaulay, 192).

After a central and climactic section set in Cambridge the novel's concluding postscript returns the reader to Dean Prior to where Herrick has returned from Cambridge. It is now 1647 and the poet is preparing to leave the community after his expulsion:

Mr Herrick ... was at last to be ousted as a superstitious scandalous malignant and delinquent minister, who refused the Covenant, and a Buckfastleigh weaver would pray and preach in Dean Prior Church. It was a scandal, the squire and his wife agreed (p.436).

I had not known of Rose Macaulay’s fascination with Herrick, nor been aware of the existence of her novel based on him and his time in Devon, until my recent exploration of the place and poet. It was therefore with considerable interest that I read her own imaginative historical recreation of the era and setting in conjunction with Herrick's work. It seemed to me that her narrative authentically recreates the prevailing temper of the time, both in terms of local responses to the turbulent fervour occasioned by the dispute between King and Parliament and also in the way she presents the wider Devon community. It almost seemed as though one could reach out and back and for a moment intuit the thoughts and responses of forefathers who had lived in and around Dean:

The Dean men had mostly been back for over a year, sullen and rebellious against those who had dragged them into this foolish fighting. They cared little for King or for Parliament, Church or Presbytery; all they wanted was to be left unmolested on their farm and fields and allowed to carry on their lives, delivered from the burdens of garrison, quartering and plundering ... Such was the west-country farmers' view of the war (436-8).

Macaulay was recovering lost fragments of her own distant past just as I'm attempting to recapture a personal lost world in this blog. She did indeed visit Dean Prior a year before the novel was published, so presumably whilst she was immersed in its writing. Her re-examination and revivifying of Herrick in Devon is especially understandable because she was related to his family; rather like my own involvement with the place hers initially seems to have been initiated through her need to pursue her ancestral past and perhaps seek some re-evaluation of her writerly identity by means of examining the life of the once poet, who had been her ancestral distant cousin. Her novel is dedicated to her uncle 'William Herrick Macaulay'. Apparently her great-grandfather Aulay Macaulay's wife Anne Herrick was of the same family as that of Herrick the poet.

Those who are familiar with They Were Defeated may wonder why I have not brought Julian Conybear, the young would-be poet and central tragic heroine of the book, into my discussion about Macaulay and her Devon novel, given that it is Julian as well as Herrick the poet who provides the central impetus to the plot. I've decided to postpone talking about Julian until a later blog piece. This one is already becoming rather lengthy and Julian - along with Herrick's Julia - will take me into different writerly territory. Sufficient to say that the whole book and in particular, its representation of the poet and the young girl heroine is 'an imaginative synthesis of fiction and biography' (LeFanu, 197). That success may stem from the writer's own identification with its characters for she remarked that 'Julian's own story and end were very near my own heart'. (197) Her projection into her main female character is accentuated through her choice of her own mother's surname, Conybeare. How family and fiction can interweave!

....

As sometimes happens, via a string of strange coincidences or synchronicities, as I came to the end of my research for this blog and began to write it up I discovered another serendipity between the Dean Prior writers and their worlds and other familial branches of my own ancestral tree. One of Robert Herrick’s Devon friends – and possibly the contact who provided the initiative for the poet to come to the county in the first place, was the Revd. or Dr John Weekes, rector of Shirwell. Weekes - or Wykes - was from one of Devon’s oldest, and prolific families, whose main estate at the time was at North Wyke in mid-Devon. According to some sources Herrick sought sanctuary with his friend when he was expelled from Dean. A branch of the Weekes family had sprung up in the Broadwoodkelly - Honeychurch area and although the Weekes genealogy is complicated it seems that Herrick's friend was a son of the latter branch; his parents have been identified as Simon and Mary Weekes of Broadwoodkelly. My paternal Sampson ancestors for the most part came from Broadwoodkelly and Susannah Weekes, from one of the local Weekes' branches, married into my family at the beginning of the C18. So, the possible perturbations of Robert Herrick's Devonshire life as it may have intermingled with lost lives of my own ancestors extend out even more and leave me with much food - for finding forefathers and foremothers - thought.

... As I leave this post I remember that Mary Lady Chudleigh Devon's proto-feminist poet was married at the age of 18, in 1674, the same year the Herrick died and that the Chudleigh's family estate, Place, at Higher Ashton, was some twenty miles up the rural roads from Dean Prior. Herrick may well have known and visited her husband's family on occasions when he visited Exeter; after all the Chudleighs appear to have been staunch Royalists, as was he. As it happens Chudleigh's writing lies waiting at the back of my mind, in preparation for my next blog-piece...

ps There will be more photos here later ...

No comments:

Post a Comment

Do send feedback on this blog.